What’s in a Name?

Re-examining our past to envision a better future

What’s in a Name?

The History Behind Memorial Episcopal Church’s Name and Why we feel it is time to re-dedicate this space

Over the last two years, Memorial Episcopal Church has dug heavily into our history in order to better understand what has come before us and to seek to answer a very simple question: “Why, in a city that is more than 60% African-American, in a neighborhood that is almost 50% African-American, is our congregation predominantly white?” While acknowledging that the roots of this are multi-faceted and complicated, we also recognize that our parish’s role as a leader in the segregation of our church, neighborhood and city for more than 100 years is a significant part of the answer.

This congregation has done some heavy lifting over the past few years. In intimate conversations, sermons, Liturgies in Living, community events, Vestry meetings, ceremonies and retreats, we have been wrestling with the truth of our history. We have uncovered, carefully considered, and publicly acknowledged that racism is interwoven with Memorial Church’s history, and that we desire to disentangle ourselves from that past and mark a new path for the future.

We know that our history includes, but is not limited to: .

The men for whom this Church is a Memorial enslaved people and, as did several rectors to come, actively supported the Confederacy and the institution of slavery.

The fact that our church was founded, in part, as a breaking up with the abolitionists in our ‘mother church’ down the hill in Mt. Vernon

Our longest serving rector, William Meade Dame was an avowed segregationist who sought to keep the Church, the neighborhood, and the city, white.

Historical vestry minutes clearly show our ancestors promoted discriminatory real estate and neighborhood design practices that were designed to “protect the whiteness of Bolton Hill” and they even fired a rector who tried to welcome our African American neighbors.

As the 21st Century members of this community, we have a choice. We could continue to whitewash the stories, to gloss over with “that was then, this is now” platitudes. Or, we could face them with courage. Below you will find some detail on a few periods of our history, and then discussion about what is next for Memorial and how you can be a part of the conversation.

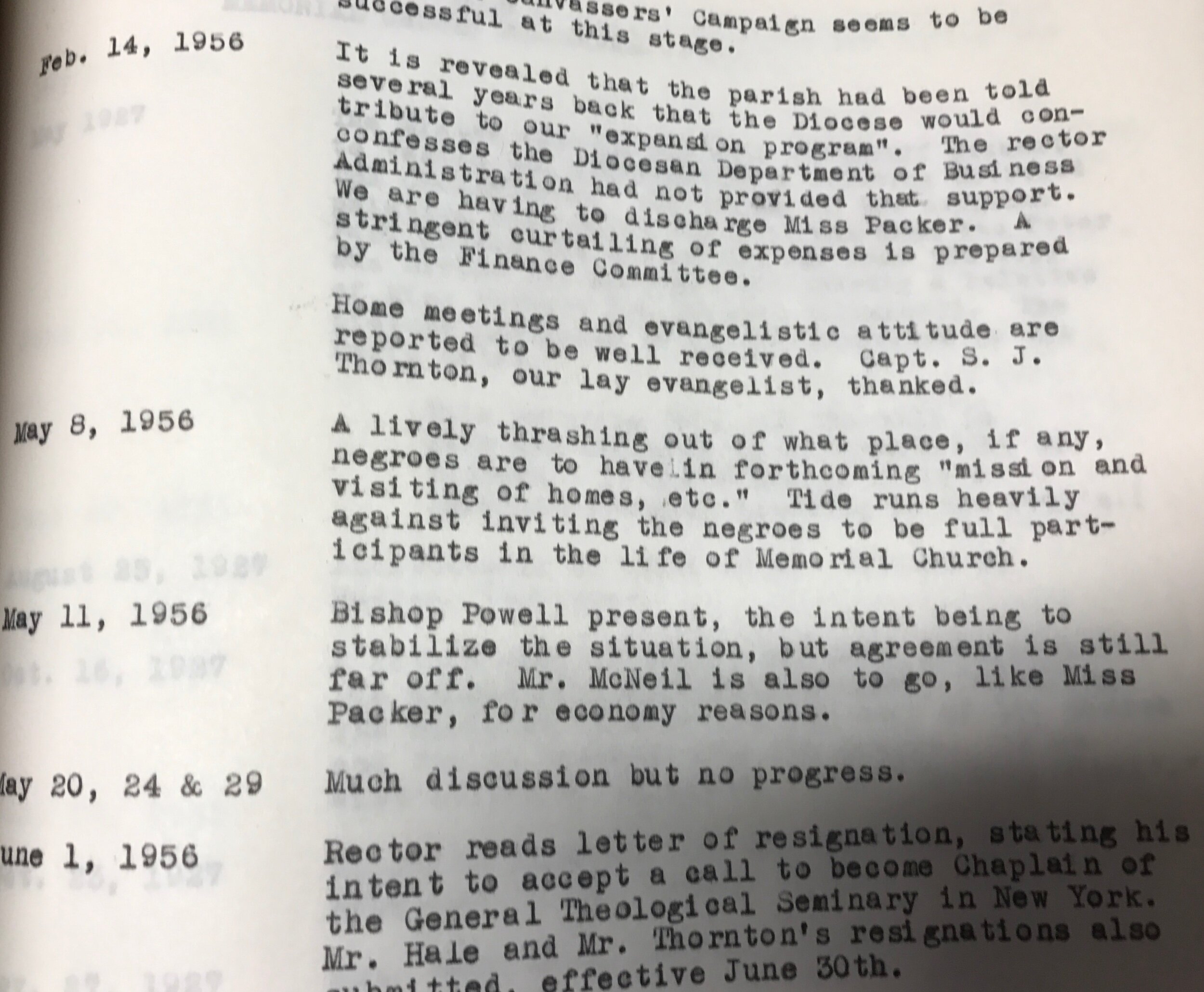

Vestry Minutes from 1956

These minutes from a meeting with the Bishop describe the racist attitudes of the parish members when they were asked to integrate the church in 1956.

Rather than accept a large grant from the National Church to evangelize the local community and expand the Church, they fired their Rector and associate in order to keep the parish and the neighborhood white.

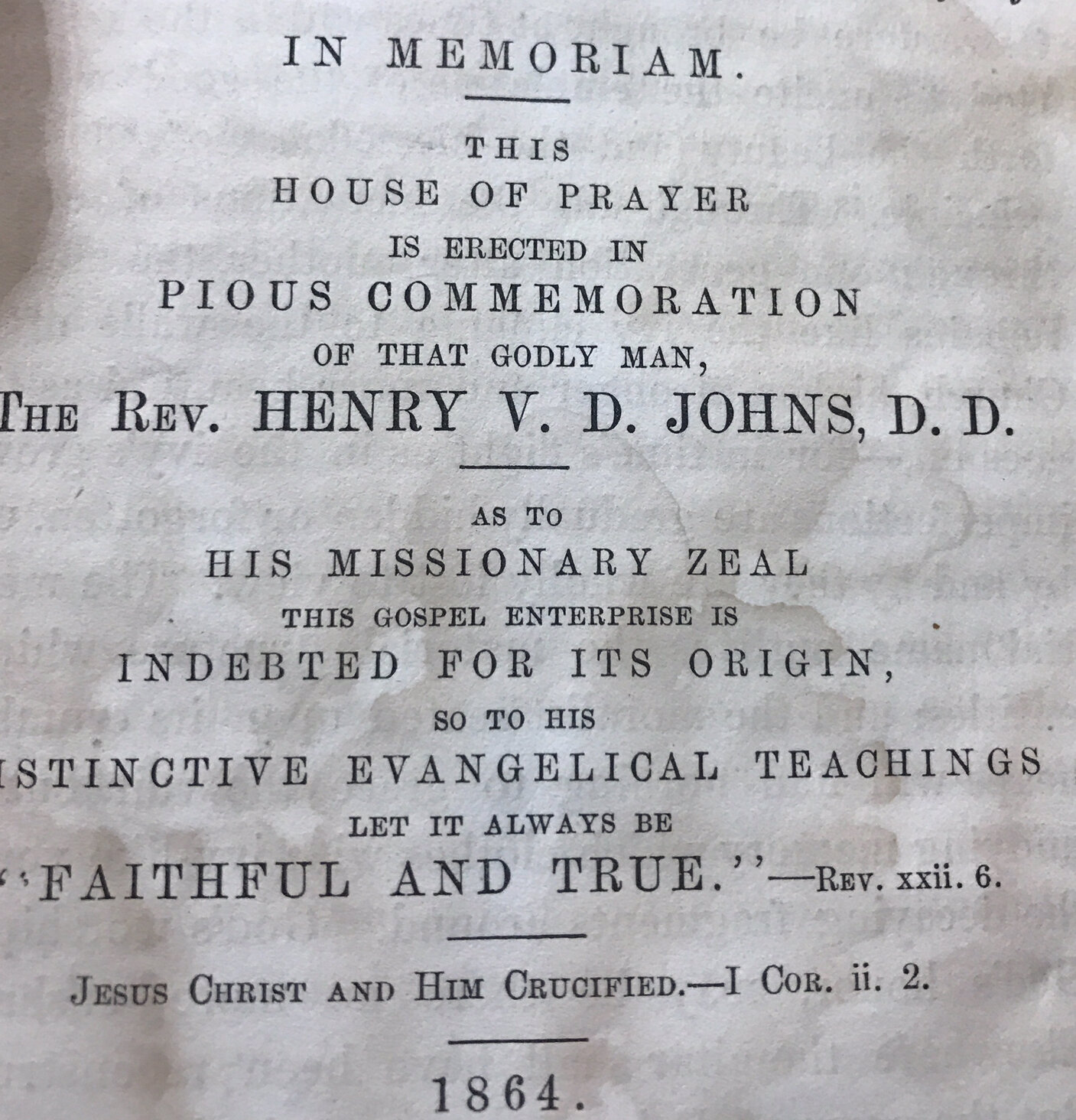

About the Founding of memorial

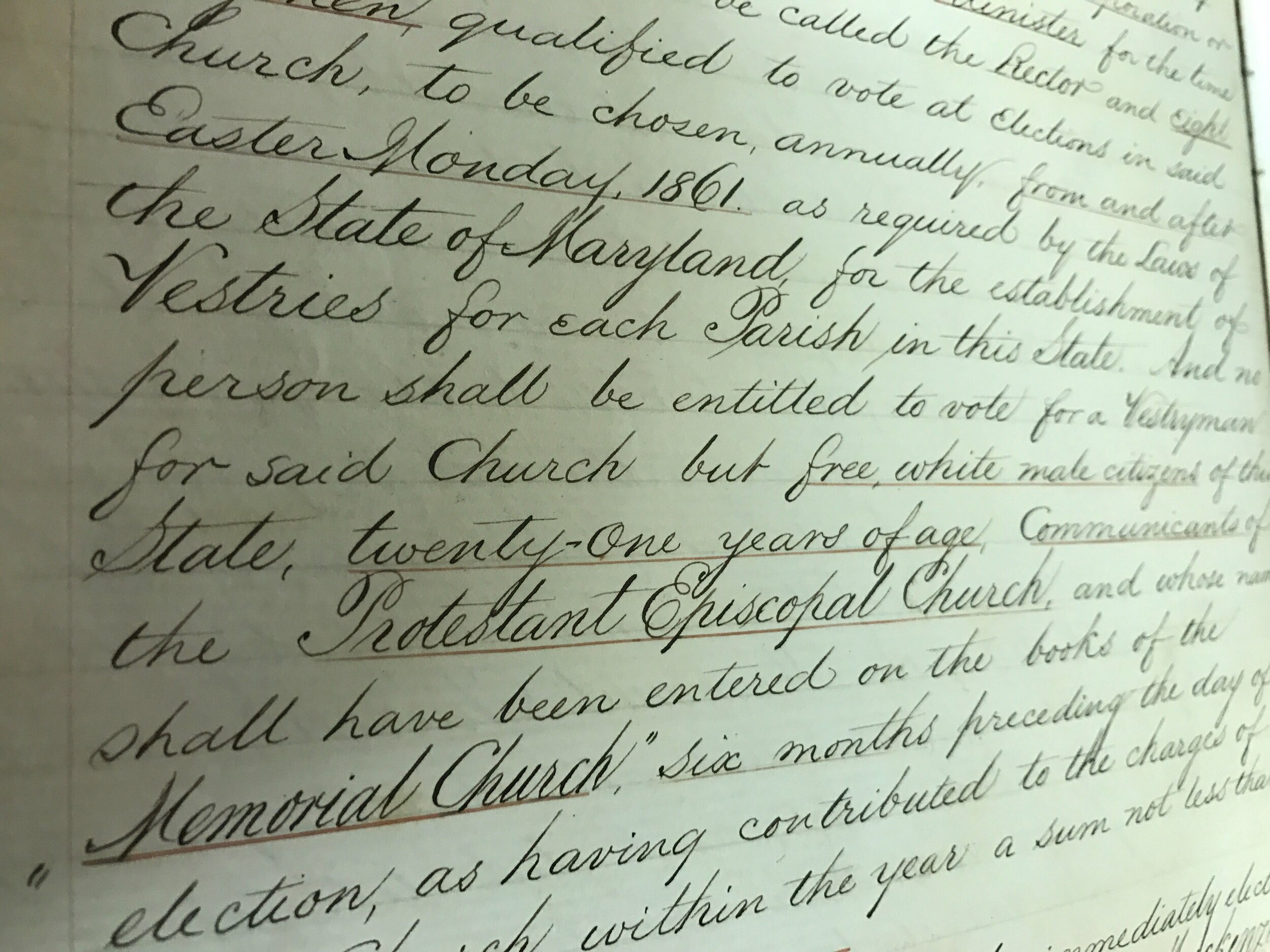

Memorial was founded by members of Emmanuel Episcopal Church and was dedicated on Easter Weekend 1860. Memorial’s original constitution specified that the only voting members of Memorial were free, white, property owning white men over the age of 21 years of age.

The founding Rector, The Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard was a Southern sympathizer, a slave holder, and the new Rector of Memorial Episcopal Church. The church was a recently planted mission of Emmanuel Episcopal Church and was named as a Memorial for Henry Van Dyke Johns, a conservative low-churchman who was himself a slave holder and the brother of the Rt. Rev. John Johns, Bishop of Virginia, Chaplain to Robert E. Lee and in many ways the ‘Bishop of the Confederacy.’ The Rev. Howard saw his role to be a ballast against change and a support for other Confederate sympathizers. He was the son of James Howard, and grandson of John Eager Howard, Revolutionary War hero and Governor of Maryland. The Rev. Howard’s mother was Sophia Gough Ridgely, daughter of Charles Carnan Ridgely, former Governor of Maryland and master of Hampton Plantation. Between the two families, they enslaved more than a thousand people across multiple properties in the greater Baltimore area. After his death in 1862, the Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard was buried at Hampton Plantation, which at that time was home to more than 400 enslaved people.

Among those families enslaved at Hampton Plantation were the Cromwells, who like many, were not freed until after the Civil War was over. Approximately 155 years later, The Rev. Natalie Conway walked in to Memorial Episcopal Church to serve as Deacon at the altar under a roof dedicated to the minister of God whose family, unbeknownst to her, had enslaved her ancestors. When the Truth came to light, The Rev. Conway was shocked. And so were the rest of us.

Ms. Hattie Cromwell

Ms. Cromwell is the great great grandmother of The Rev. Natalie Conway, she was enslaved at Hampton Plantation until 1829 when she was freed by manumission upon the death of her master.

She and The Rev. Charles Ridgely Howard were both born at Hampton Plantation, but under drastically different realities. Now both her great-great granddaughter and an indirect descendant of Rev. Howard (Charles had no children) are members of Memorial.

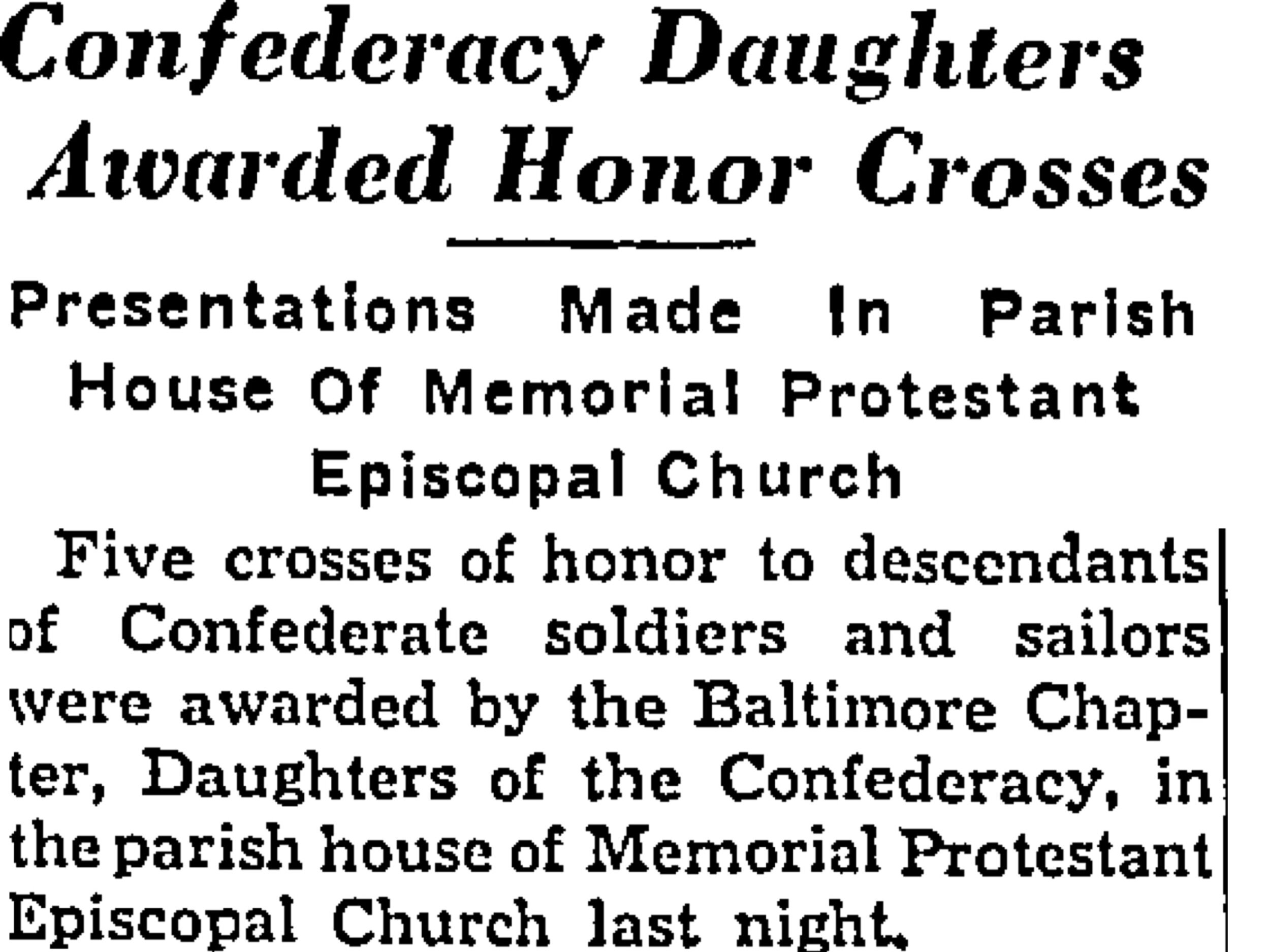

Continued Support for Segregation

Memorial’s legacy continued long after its founding. Seven of the first eight rectors served in the confederacy. It was not until the 1940s that the Church had a leader who was not directly connected to the Confederate army, and the parish remained intentionally segregated until 1969.

In 1909 Maryland was debating a hotly contested amendment to the State Constitution. There was a strong movement supported by many conservative men (all men) of the cloth — to restrict the right to vote to white men only because ‘I do not think there is any doubt to the fact that the negro is best out of politics, and I believe this amendment is the fairest and best they could have drawn’(The Very Rev. Ferdinand Lintz). Good progressive white men from across Baltimore all agreed that this was what was best for the black population of our city.

The amendment in question was carefully constructed to do two things: 1) make sure the vast majority of Black men in Maryland could not vote; and 2) not mention the words ‘black, negro, colored’ or any other variation in the text. It did so by implementing an ‘education test’ for voters — but one that ONLY applied to those given the right to vote after 1869 and excepting those who were not born in this country. It was not particularly subtle and those speaking in favor of the resolution were not subtle either.

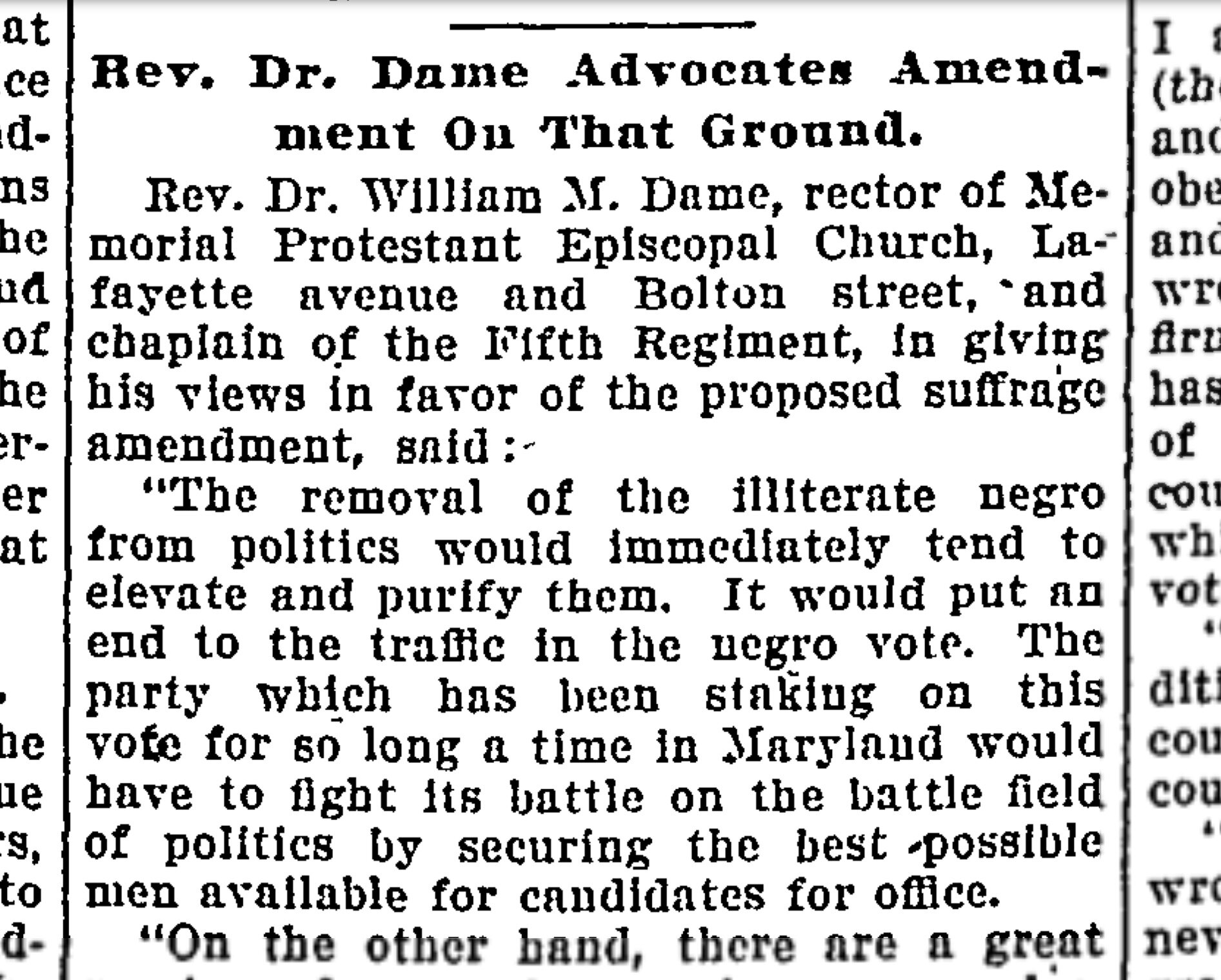

On the day of the amendment vote, The Rev. Dr. Dame offered his own comments, in a letter published in the Baltimore Sun, saying ‘the removal of the illiterate negro from politics would immediately tend to elevate and purify them.’ Condescending and pejorative — he cast his neighbors as poor, illiterate, suffering folk who don’t know any better. The Reverend continued saying that the amendment by no means stripped the negro of the right to vote, because ‘the people would not stand for it if the negro were eliminated from politics’ For Dr. Dame and others like him this was a ‘temporary measure’ for the ‘good of the country’ that didn’t ‘target negroes specifically’ and that most importantly would help to ‘’heal deep divisions’ in a state of politics that had ‘never been more divided.’

Dr. Dame’s Letter Supporting Voter Disenfranchisement

What is the rest of the story?

Here we have lifted up and acknowledged much of the terrible portions of Memorial’s story. But we also must acknowledge that a Memorial was a significant and important part of city and diocesan life in this period. And as in any institution, there were many people who sought to change the segregated reality of the parish and the neighborhood. Arthur Kelsey and Sam Hale came here to serve in the 1950’s hoping to create a new kind of community. Parishioners like David and Dick Roszel and the Shivers, and the DeMuths gathered in the 1960s to dream about a different kind of church that would embrace the whole community. They saw in Memorial a community that was deeply committed to the community around it, and helped it to envision a different kind of reality for that community, one much more like our surroundings today.

Memorial also in its first hundred years produced three Bishops and four mission parishes in a Baltimore to spread the gospel and the Episcopal Church across the city. Two of those buildings, including St Katherine of Alexandria, now house historically Black Episcopal Churches in Baltimore. In spite of ourselves, God has done some good things through Memorial’s ministry and Memorial’s story.

This is an important reminder that redemption is possible in Memorial’s story, just as redemption is possible in all of our stories.

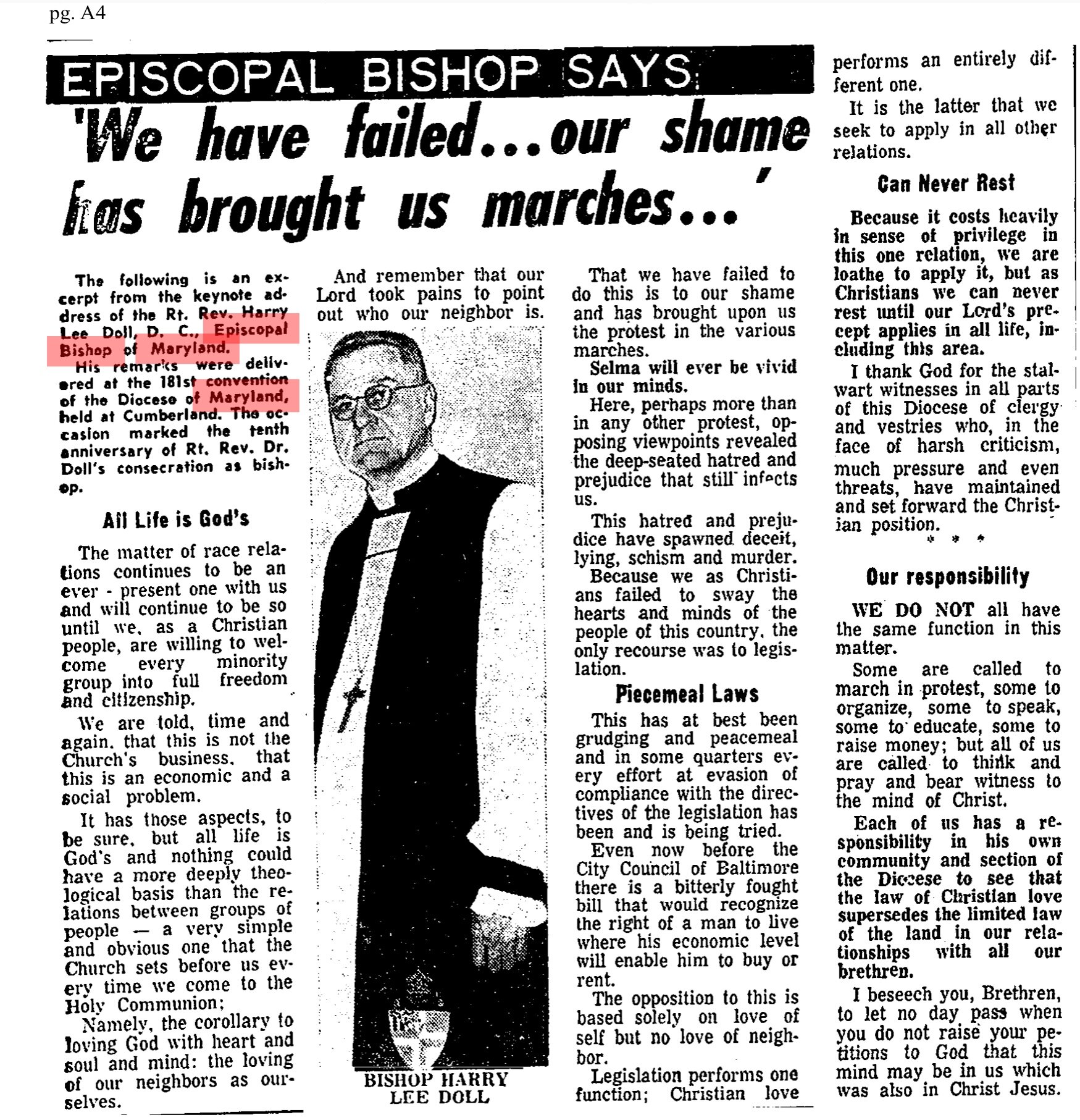

Bishop Doll’s Response to our past

It is important to remember that the Episcopal Church did many important things in this period of history, and had many leaders who had called attention to racism, to segregation and to the need to be God’s Kingdom.

Bishop Doll recognizes this while also calling the whole church to be better and to not rest in our call to be the Kingdom of a God.

The Bishop of Maryland’s Response to Memorial Conducting a Same Sex Blessing in 1992

In 1992, The Rev. Bill Rich conducted a blessing for two women in Memorial’s Sanctuary on the 4th of July. Independence Day.

In response the Church and clergy were reprimanded by the Diocese and the following instructions were given.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1992-10-30-1992304044-story.html

The Last 50 years

We also acknowledge that this congregation has, in the course of time, taken actions that INCLUDE rather than EXCLUDE people. And some of these decisions were “cutting edge” and controversial at the time, but they helped the larger episcopal community change. We are the church:

That called the first female priest in the Diocese

That ran draft clinics and helped Vietnam War protestors fight their draft numbers

That welcomed the first openly gay priest in Maryland and supported his ordination

That blessed same-sex unions in 1992, celebrated LGBT weddings in 2003, and, later, when it was finally legal in Maryland, conducted one of the first legal Same-Sex weddings in the State of Maryland.

And, that stood in love with two of our members, Steve and the Rev. Natalie, as they poured holy water on the ground at Hampton Plantation, symbolizing our journey toward healing, reconciliation, and respect and care for one another.

These efforts were spurned on by the Rev, F Lyman Farnham, known to all as ‘Barney’. He was called to Memorial in the wake of the Martin Luther King riots in Baltimore and his first act as rector was to formally integrate the Church, inviting the Pastor of Sharpe Street Methodist Church, the oldest African-American Church in the city, to co-preside at his installation. Memorial’s recent history has been one of taking courageous inclusive actions, despite whatever controversy they might stir, to be an example of an evolving, atoning, stepping toward redemption, just as Jesus instructs. For many members and friends of Memorial, this is the Memorial they know and the reason they are proud to be a “Memorialites.” It is reasonable, even understandable that they would feel a certain level of concern about the name Memorial.

What’s Next?

But we are not finished.

At the 2020 Annual Meeting, the vestry proposed that this congregation Re-Dedicate our Memorial Church. We do not propose a white washing of our legacy. We believe it is necessary to remain aware of our legacy, if for no other reason than to help (now and in the future) avoid perpetuating the pain of racism.

Instead, the Vestry proposes re-examining what this church is a memorial to and should be to, and collectively re-dedicating this building and ourselves to that.

Between now and March 15, 2020 you are invited to give your thoughts about this to a member of the Vestry and/or to our rector. You may write a letter, send an email, call or talk to us in person.

We will host a Liturgy In Living discussion during Lent, on March 15, to discuss the feedback and possible dedications and memorializations.

At their February and March meetings, the Vestry prayerfully consider all feedback and ideas about what exactly it is that we collectively want to re-dedicate this place.

On Easter Sunday, April 12, we expect to announce the Vestry’s decision. This date is significant because it is almost 160 years to the date of the original founding of Memorial.

In late Spring, we will formally gather to affirm this decision and re-dedicate our space and our lives.

In the Fall of 2020, we hope to be able to physically symbolize this with some changes to our facility.