Acknowledging our Past

Repairing our Future

Repentance and Reconciliation

Becoming A ‘Memorial’ For Everyone

More than 150 years ago, an Episcopal preacher stood up on Sunday and read from the book of Joel: “Proclaim ye this among the gentiles, prepare war, wake up the mighty men. Beat your plowshares into swords and your pruning hooks into spears: let the weak say, I am strong.”

He was preaching at the outbreak of the Civil War, after a weeks’ worth of violence between Confederate sympathizers and the occupying Union Army here in Baltimore, MD.

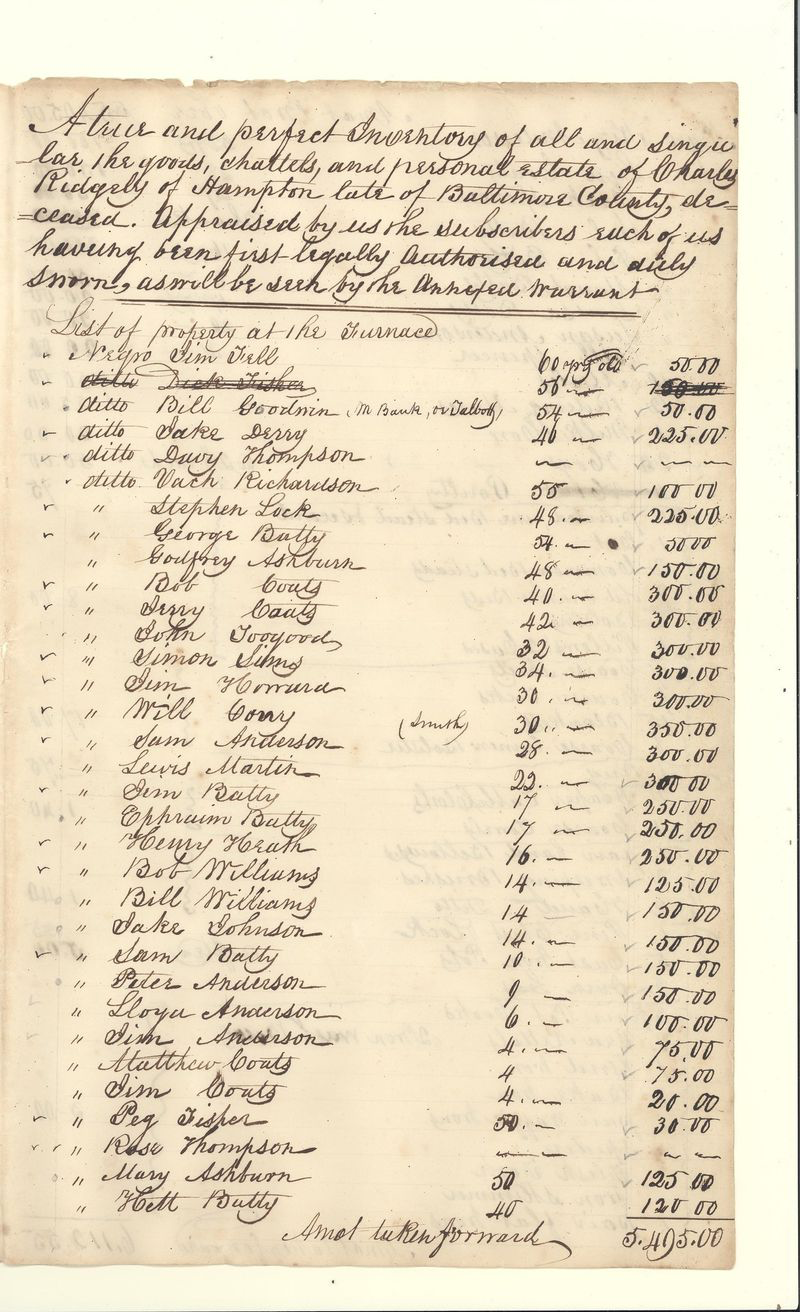

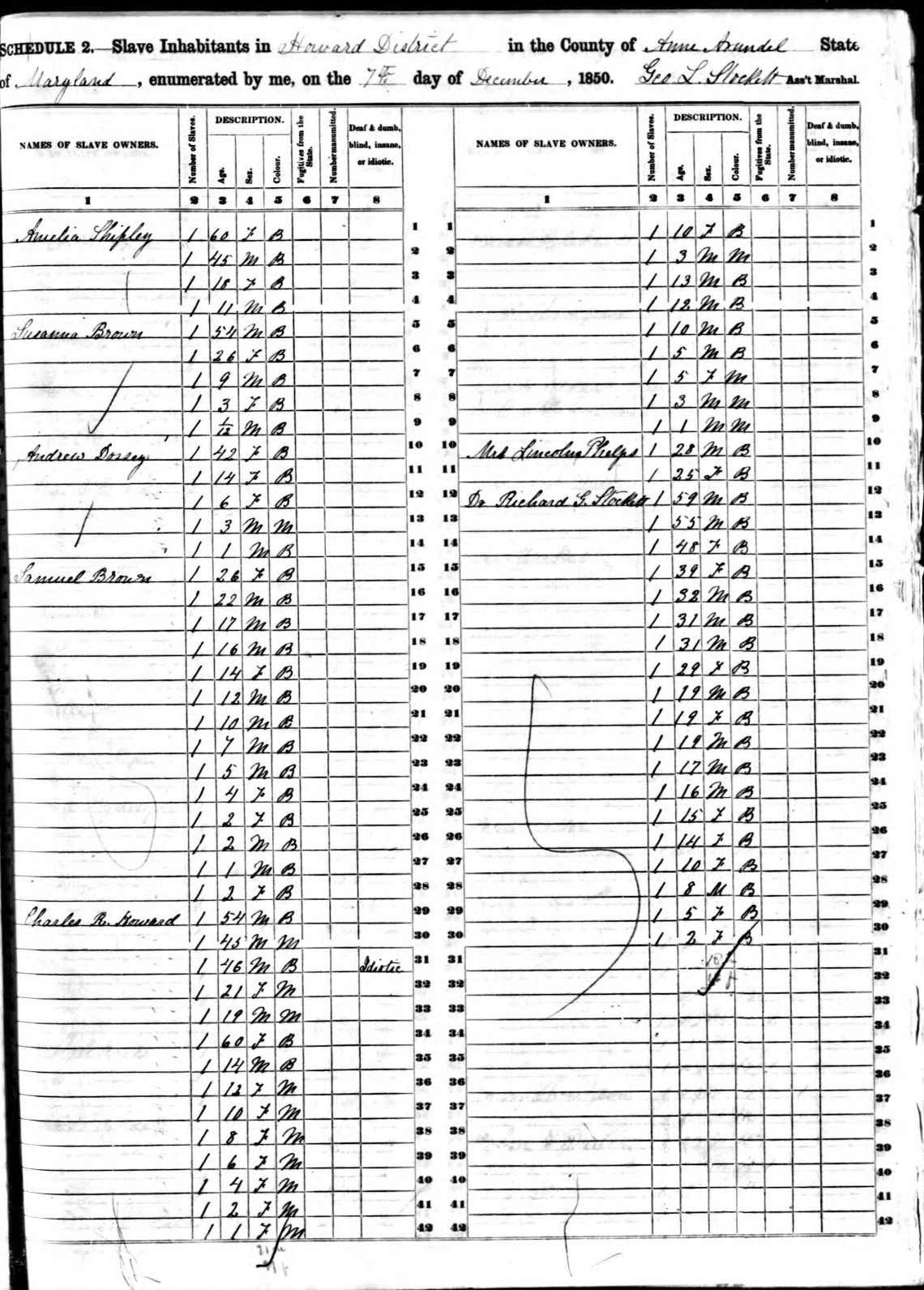

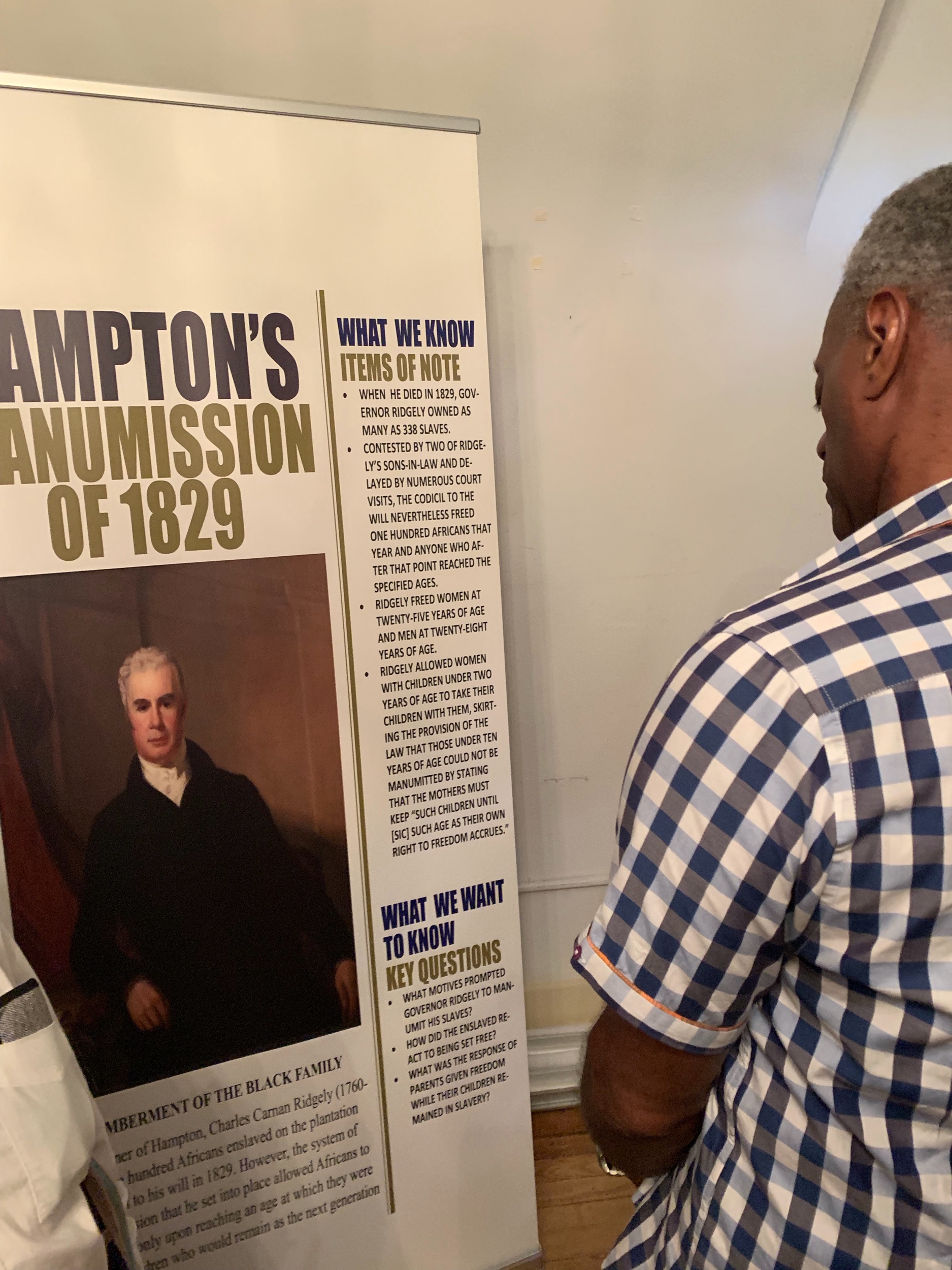

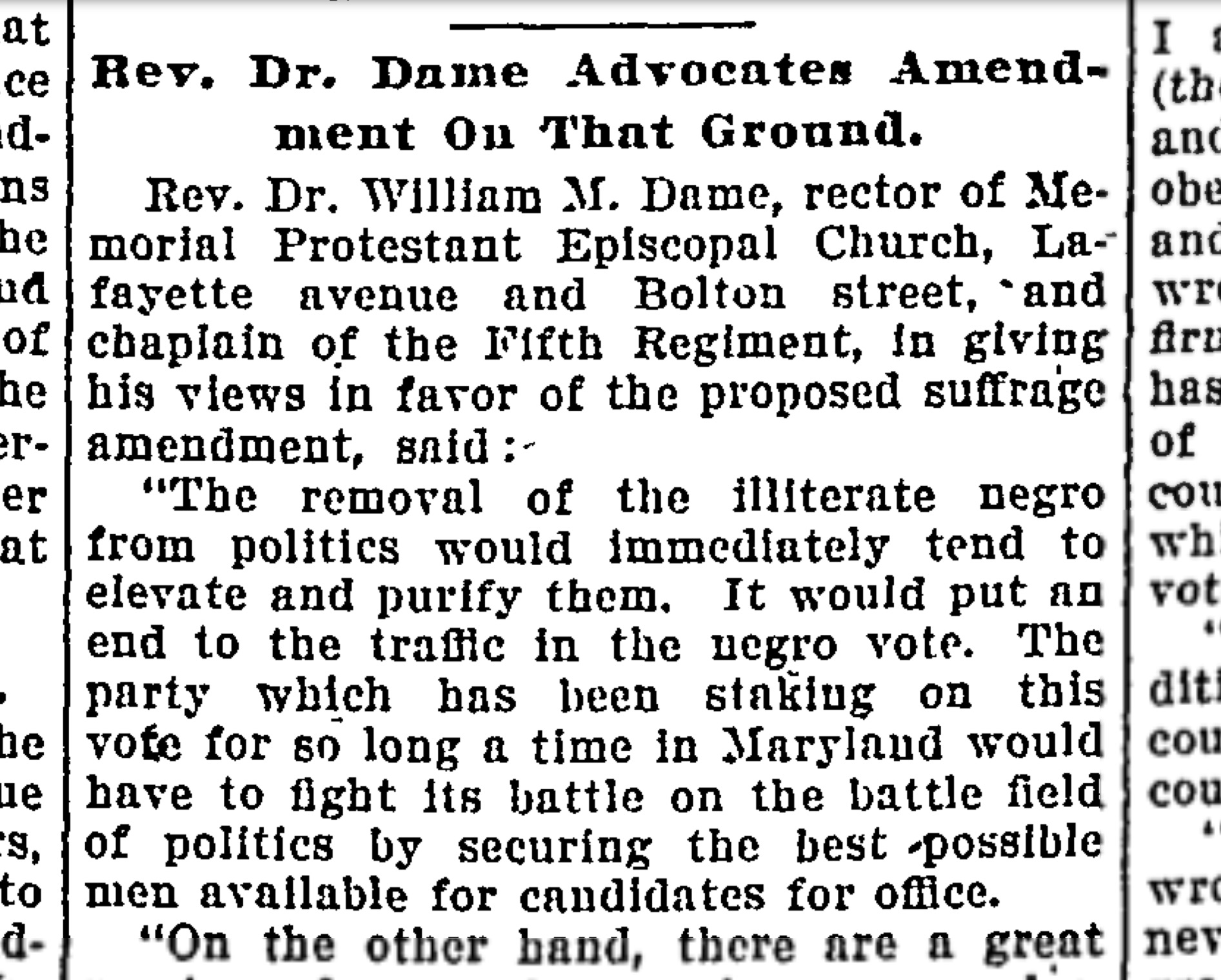

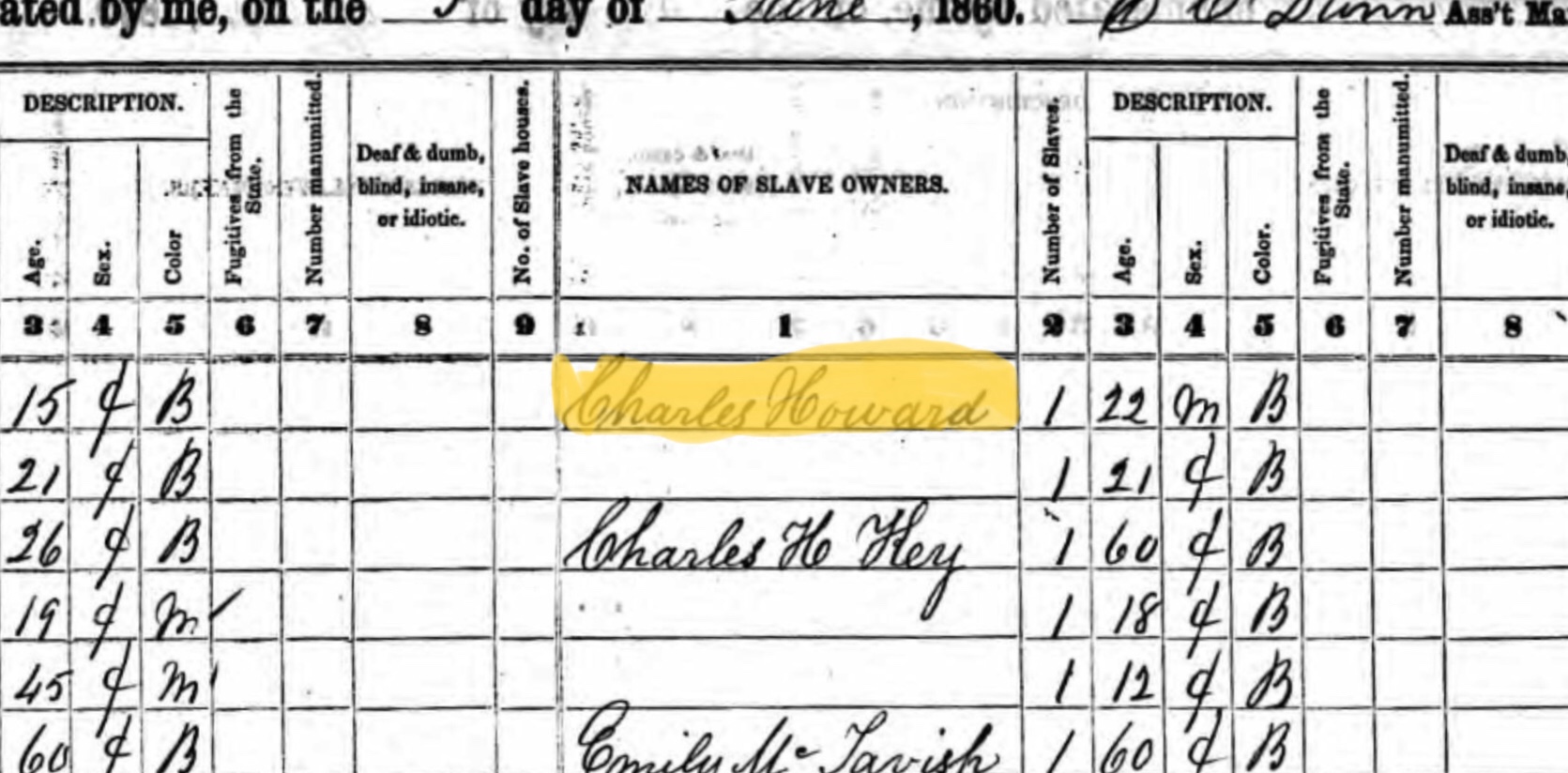

The Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard was a Southern sympathizer, a slave holder, and the new Rector of Memorial Episcopal Church. The church was a recently planted and named as a Memorial for Henry Van Dyke Johns, a conservative low-churchman who was himself a slave owner and the brother of the Rt. Rev. John Johns, Bishop of Virginia, Chaplain to Robert E. Lee and in many ways the ‘Bishop of the Confederacy.’ Rev. Howard saw his role to be a ballast against change and a support for other Confederate sympathizers. He was the son of James Howard, and grandson of John Eager Howard, Revolutionary War hero and Governor of Maryland. Rev. Howard’s mother was Sophia Ridgely, daughter of Charles Ridgely, former Governor of Maryland and master of Hampton plantation. Between the two families, they enslaved more than a thousand people across multiple properties in the greater Baltimore area. After his death in 1862, the Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard was buried at Hampton Plantation, which at that time was home to more than 400 enslaved people.

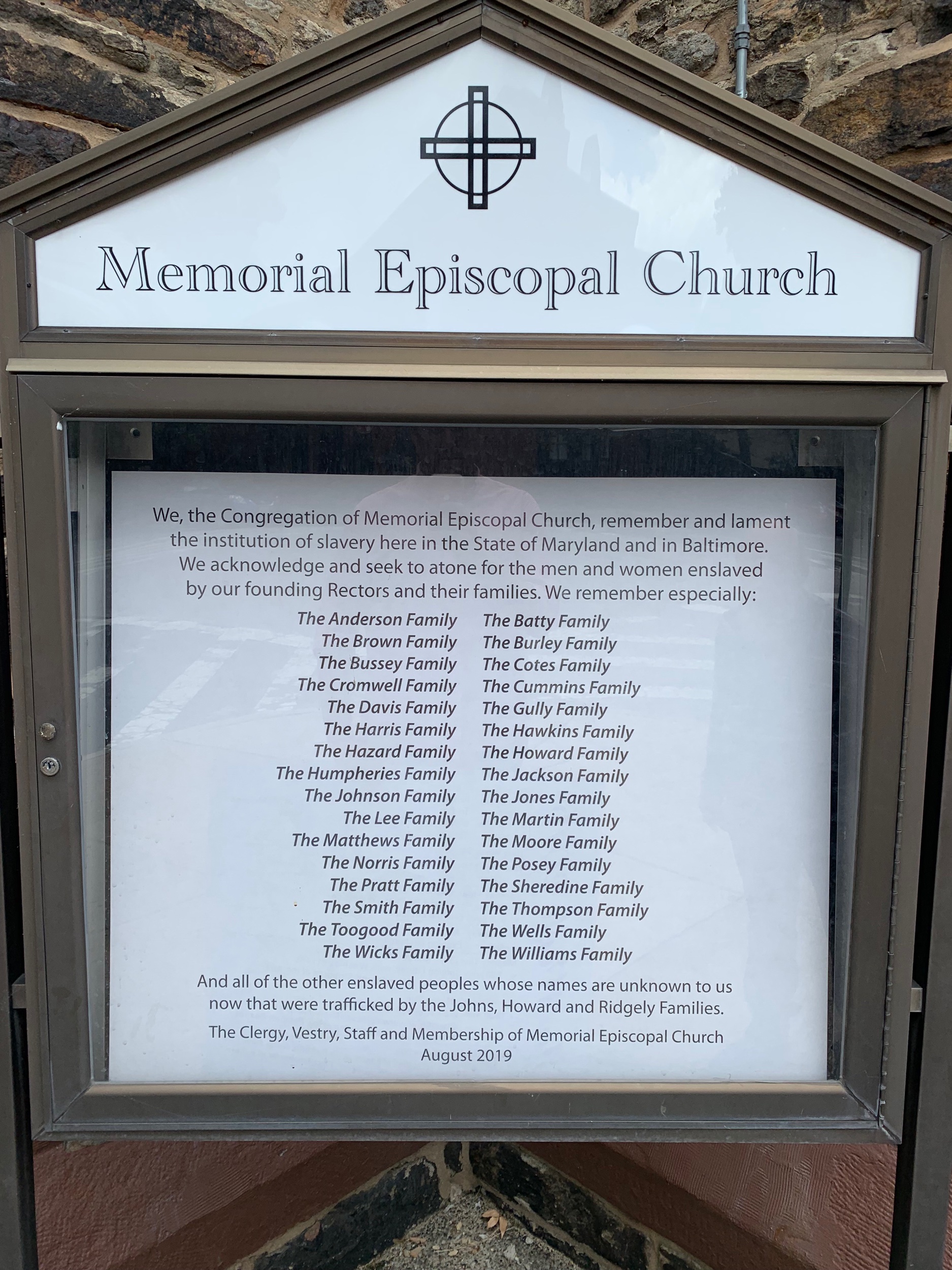

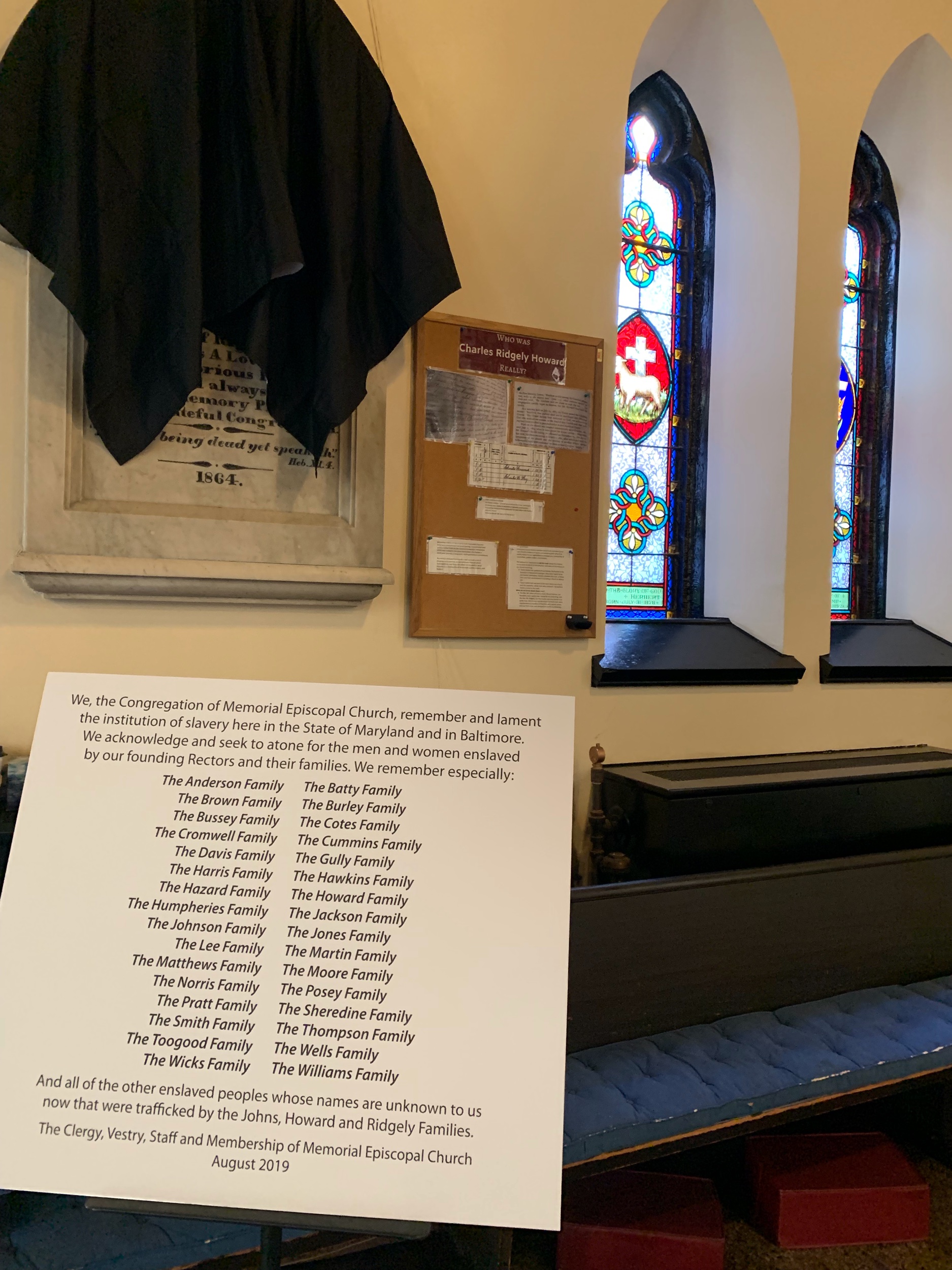

Among those families enslaved at Hampton Plantation were the Cromwells, who like many, were not freed until after the Civil War was over. Approximately 155 years later, The Rev. Natalie Conway walked in to Memorial Episcopal Church to serve as Deacon at the altar under a roof dedicated to the minister of God who, unbeknownst to her, had enslaved her ancestors. When the Truth came to light, The rev. Conway was shocked. And so were the rest of us.

Frankly, as a Church we did not know what uncovering this historical tie would mean, for Natalie, for Memorial, for any of us. However, we knew it was incumbent on us to share the truth, and prayerfully engage with it. We needed to wrestle with how it might shape our common life moving forward.

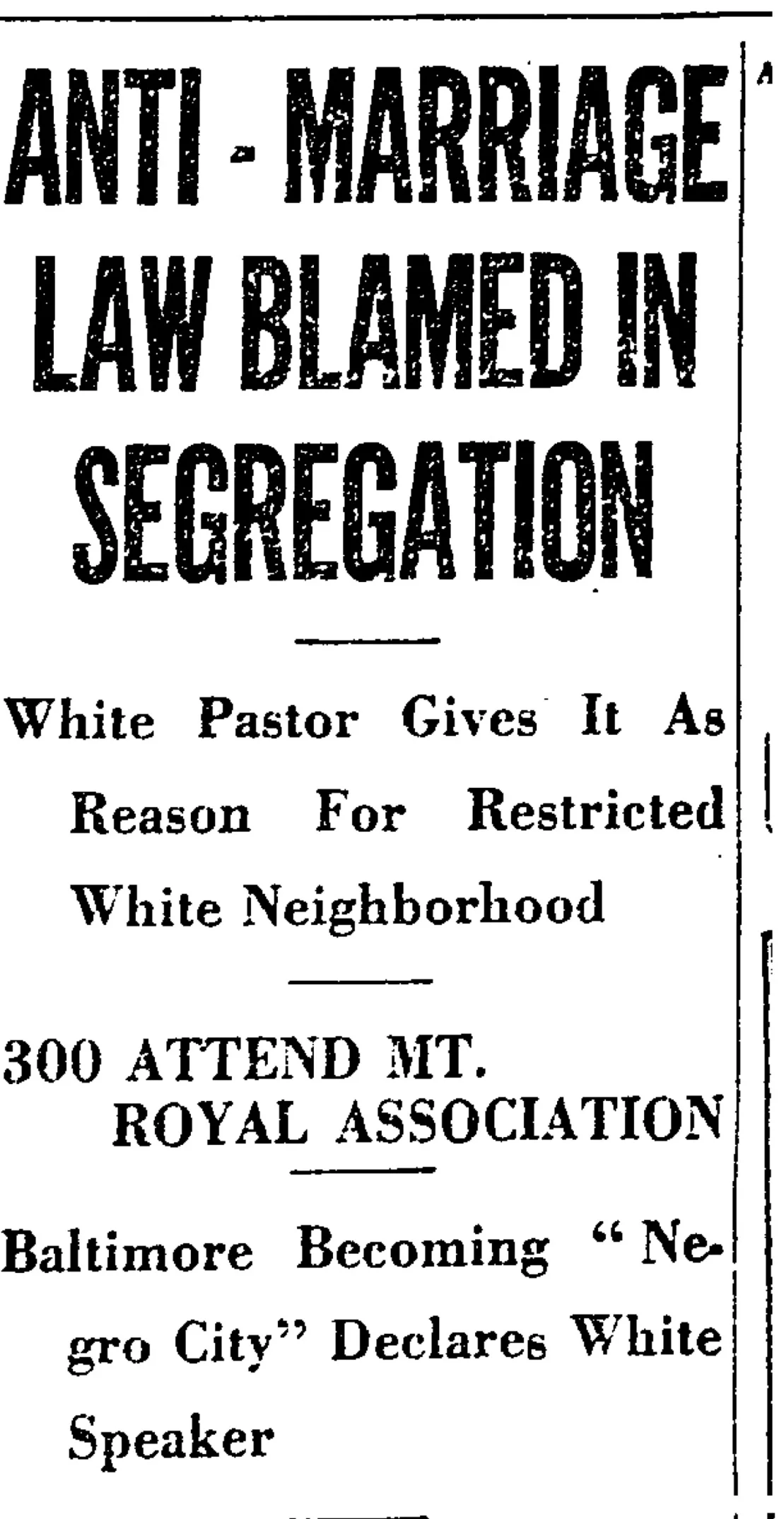

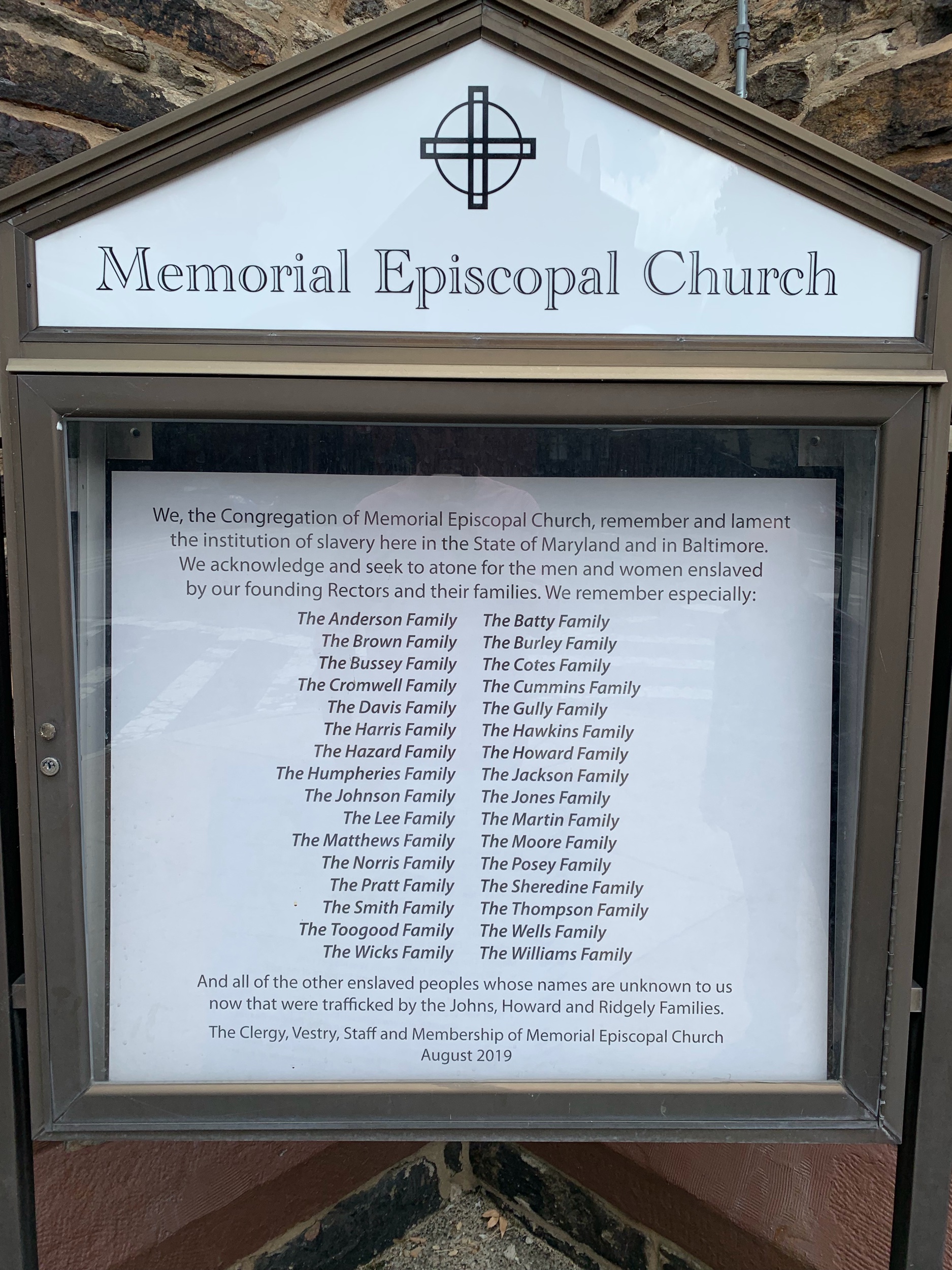

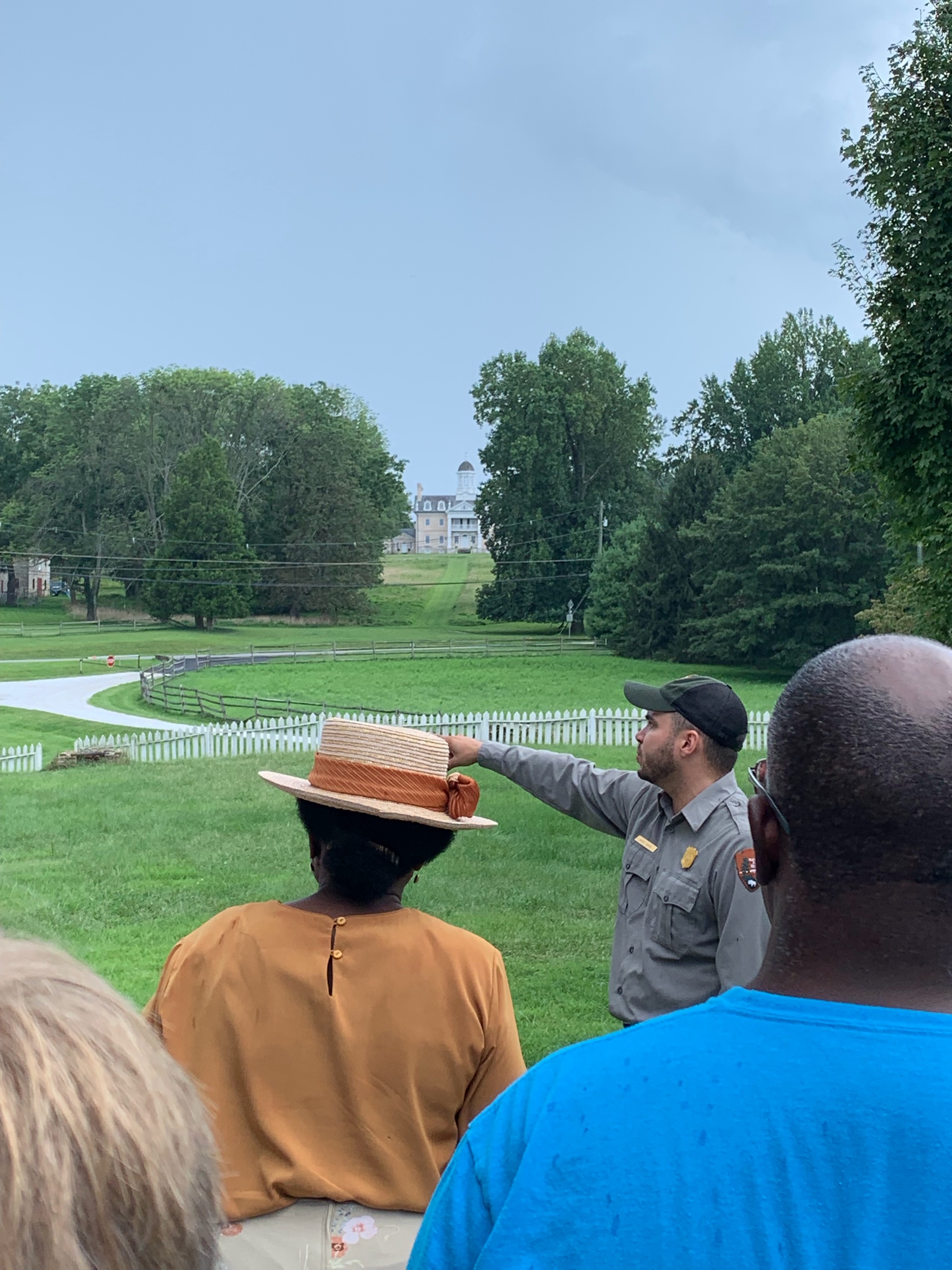

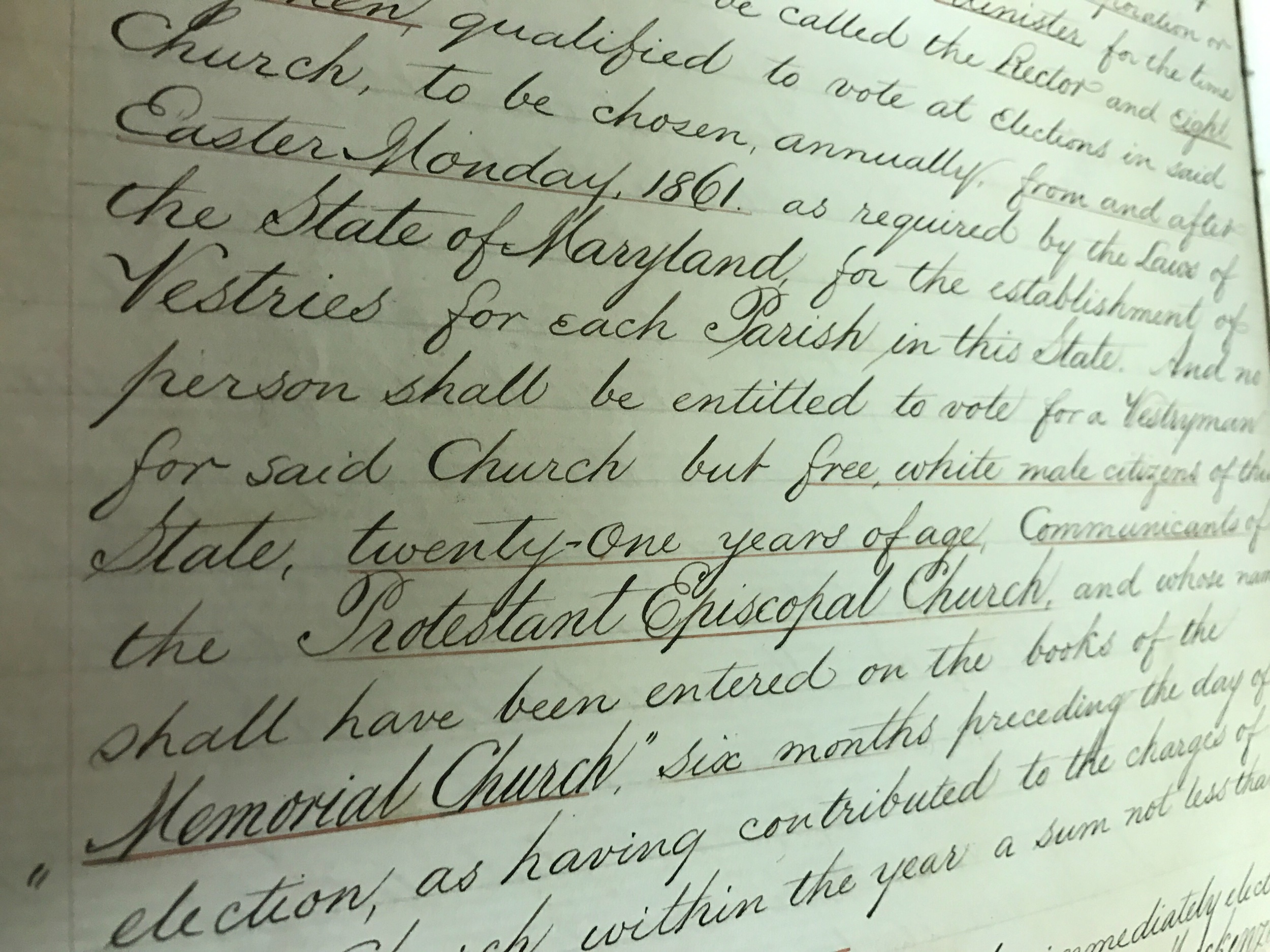

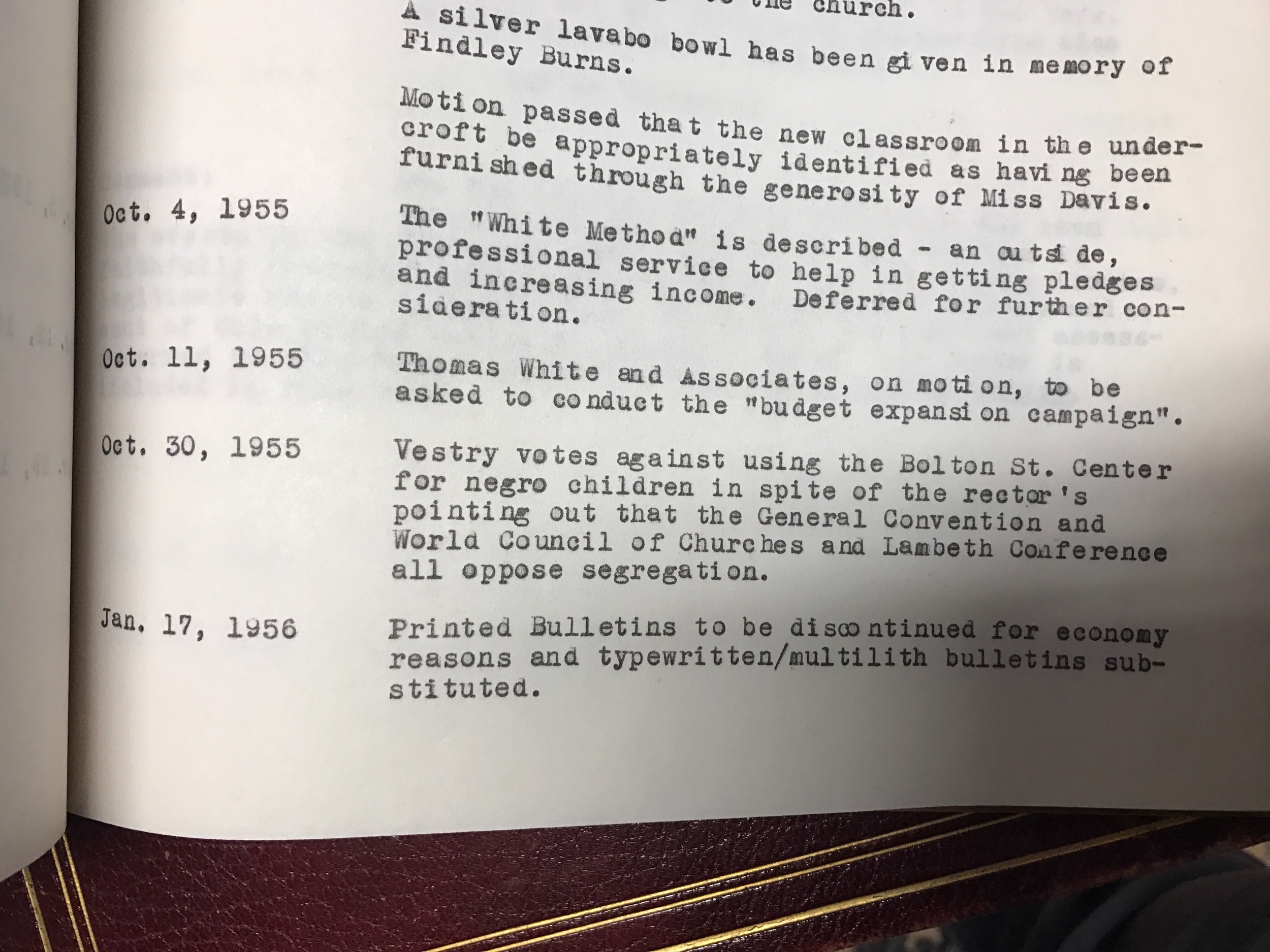

On August 18th, 2019, following services at Memorial more than 50 travelled to Hampton Plantation to the tour the property, to learn about their slave history, and to see how we might see ourselves reflected in the story. We went with a group from our sister congregation; St. Katherine of Alexandria Episcopal Church located a mile from our church. As a predominantly African American Church, founded because Memorial and others actively worked for segregation, they share in this story. , We recognize that the segregated reality of Christendom is in part because churches like Memorial began as ‘White Only’ endeavors and were kept that way far, far too long.

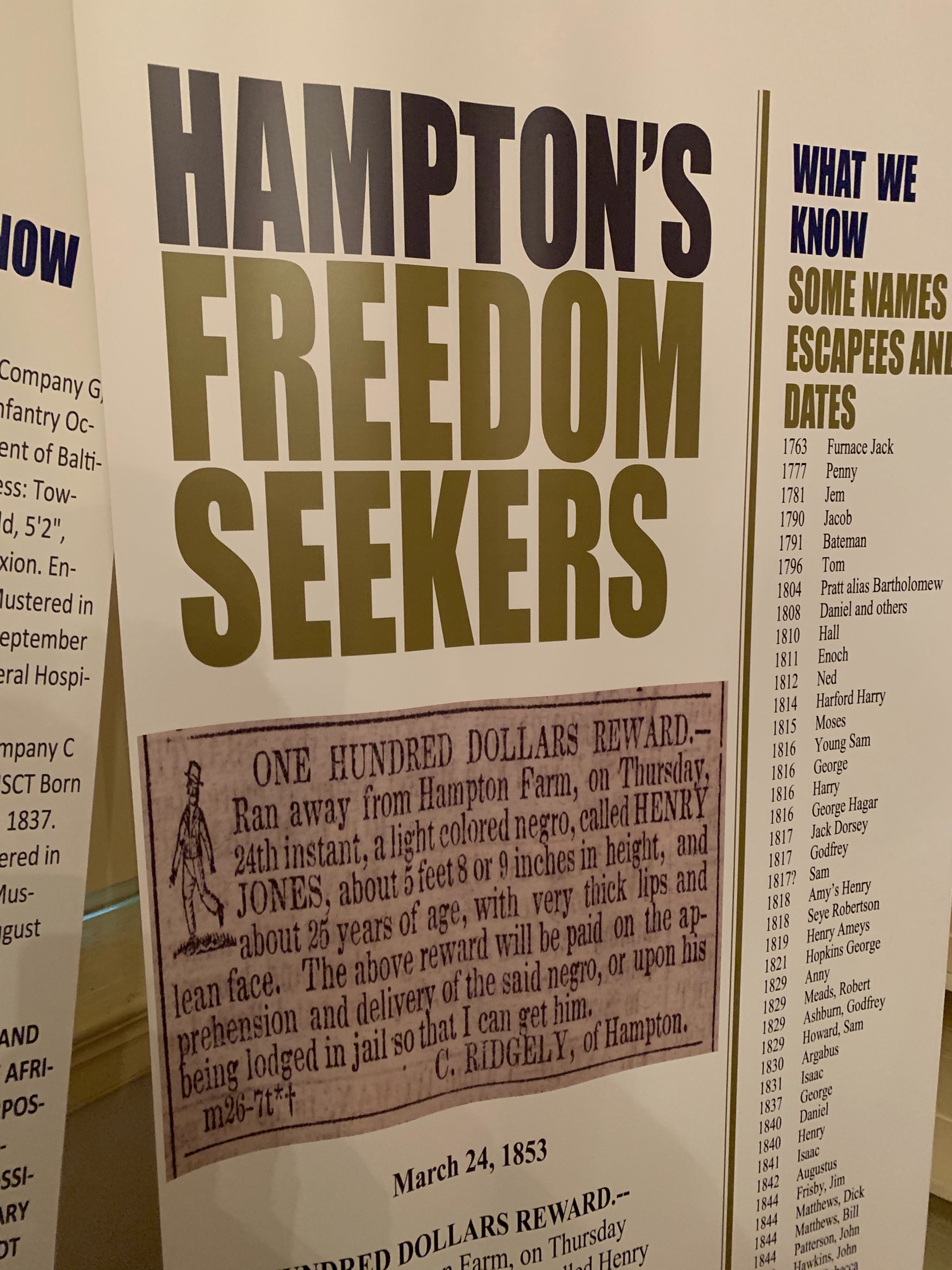

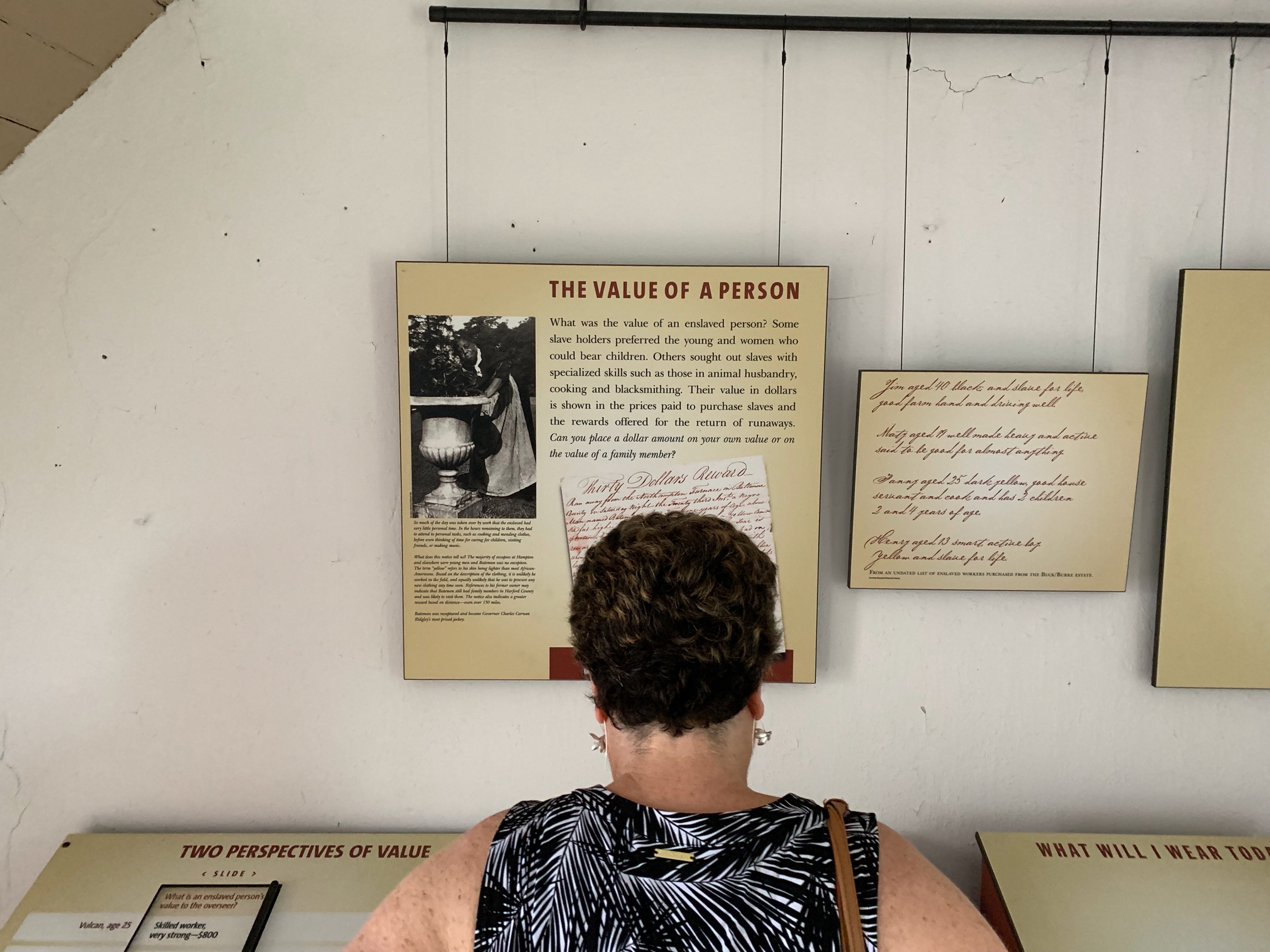

We saw the grandeur of the mansion and the beautifully manicured lands. We visited the graveyard where The Rev. Charles Ridgely Howard is buried. We saw paintings of his grandparents and his in-laws. We learned what happened to only some of the enslaved persons held at Hampton. We saw rooms where The Rev. Charles Ridgley Howard and his family might have slept--. and in contrast where Deacon Natalie’s family might have slept. We saw the chains used to hold people. The list of runaway slaves. The bell collar that frequent runaways were forced to wear. We saw price lists for slaves, tax records of their value, and the many newspaper articles offering rewards for runaway slaves.

We have so much to repent for.

For me, the most compelling signage at Hampton was a large sign that reads ‘Bondage was Bondage.’ There was no GOOD slavery. As white people we would prefer to lie to ourselves and say ‘it wasn’t that bad,’ ‘actually some slave owners were kind’, and ‘well we weren’t THOSE kind of slave owners.’ But Bondage was and is bondage, and even at a ‘ornamental farm’ like Hampton where the Ridgelys and Howards would show off how clean and well kept their slaves were - they were still more than willing to use the whip, the lash, chains and other forms of torture to subject the enslaved. And because ‘good treatment’ was only given to those who complied - it just became another form of torture, another way to instill fear and intimidation.

We finished the day in the yard in front of ‘the farm house’ next to the slave quarters, where the overseer lived and kept track of the production of the enslaved people at Hampton. Fifty of us, ages 3 to 83, gathered in a circle for a Libation ceremony. After consecrating Holy Water and offering prayers, we invited all those in attendance - some descendants of slaves, some descendants of slave owners, all of us the product of a nation and economy that began on the backs of enslaved people, to pour out holy water in memory of those who came before us. To sanctify this space and to sanctify ourselves as well.

The last two visitors to participate were the Memorial’s Deacon Rev. Natalie Conway, descendent of the Cromwells, enslaved people at Hampton Plantation; and Steve Howard, long time member of Memorial and a descendant of James Howard, father of Charles Ridgely Howard. The Rev. Conway and Mr. Howard held the pitcher and poured out the water together because of their respect and care for each other, to represent the healing and restoration of relationship between two very different families, and as a public symbol of who Memorial Church is today.

This was a momentous symbolic moment because Natalie and Steve together marked the beginning of something new. Our Church acknowledges our collective sin of slavery, and continues to work toward reconciliation through crafting new relationships, restoring things profaned, and hopefully coming back into right relationship with God as well. Sunday was a powerful exercise in speaking truth, listening more and unearthing stories untold. It also was the beginning of a new understanding of Memorial Church in our community.